Emergency physician practice and steroid use in the management of acute exacerbations of asthma

JANELLE A. THOMAS, MD,* MICHAEL W. POTTER, MD,+ FRANCIS L. COUNSELMAN, MD,* AND DOUGLAS G. SMITH, MD*

This study seeks to determine patterns of emergency physician (EP) practice regarding steroid use in the management of acute asthma ato tacks in the emergency department (ED), and to compare practices of academic and private practice EPs, Two hundred eight questionnaires were mailed to academic and private practice EPs. The survey requested information regarding the preferred initial route (oral or intravenous) for steroid administration; the initial dose of steroid; the preferred steroid regimen for outpatient management; and whether or not inhaled steroids were routinely prescribed at the time of discharge. The overall response rate was 74%; 91% for the academic EPs and 56% for private practice EPs. Sixty-five percent (99/143) of all EPs used the intravenous route for their initial dose of steroids. A significantly greater percentage of private practice EPs (45/58 or 78%) used Intravenous steroids compared with academic EPs (54/95 or 57%; P —-.009). A total of 41% (63/153) of EPs used a tapering steroid regime for Outpatient therapy; a significantly greater percentage(3458 or 59%; P — .0006) of private practice EPs used a tapering regimen of steroids compared with academic EPs (29/95 or 31%). A total of 32%(31) academic and 34% (20) private practice EPs prescribed inhaled steroids as part of their routine discharge instruco tions. Emergency physician practice patterns regarding initial steroid route of administration and dose, and outpatient-dosing regimens are variable. Only a minority of EPs prescribe steroid metered dose inhalers as part of their outpatient management of asthma. (Am J Emerg Med 2001;19:465-468. Copyright s 2001 by W.B. Saunders Company)

Corticosteroids are a mainstay of therapy in the manage- ment of acute exacerbations of asthma in the ED. Clinical practice guidelines from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommend the use of steroids in the treatment of an acute exacerbation of asthma. Rate of relapse has been shown to decrease after a discharge course of steroids.2 4 There are many different regimens reported in the literature, but precise recommendations and conclusive data regarding initial dose, route of administration, duration, and regimen for tapering are lacking.’ ^-*

The current study sought to determine common patterns of emergency physician (EP) practice with regard to steroid

From the “Department of Emergency Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School and Emergency Physicians of Tidewater, Norfolk, VA; the tEmergency Department, Sentara Hampton General Hos- pital, Hampton, VA; and the tDepartment of Emergency Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Manuscript received October 20, 2000, returned November 26,

2000, revision received December 12, 2000, accepted December

30, 2000.

Address reprint requests to Francis L. Counselman, MD, Depart- ment of Emergency Medicine, Raleigh Bldg, Room 304, 600 Gre- sham Drive, Norfolk, VA 23507.

Key Words: Asthma, ED, steroids.

Copyright c 2001 by W.B. Saunders Company 0735-6757/01/1906-0002$35.00/0 doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.24485

use in managing acute asthma attack. in the ED. Addition- ally, practices of academic and private practice EPs were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 208 questionnaires were mailed; 104 to aca- demic EPs and 104 to private practice EPs in the spring of 1997. The academic EPs selected were Program Directors (PDs) of Emergency Medicine residency programs, identi- fied by their inclusion in the 6 edition of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Catalogue of Residency Programs. The private practice EPs were selected at random from the 1996 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) Reference Guide and Member Directory. In addi- tion, respondents were required to indicate on the survey if they considered themselves academic or private practice EPs. Their response determined which category (ie, aca- demic versus private practice) they were placed in for purposes of analysis. No dehnitions were given as to what constituted academic versus private practice.

In addition, the survey requested information concerning board-certification status and type of residency training of the respondent. The survey asked participants their pre- ferred route (IV v orally [PO]) and dose for the Initial administration of steroids to treat an acute exacerbation of asthma in the ED. Respondents were asked to select a regimen of prednisone (if any), they routinely prescribe to patients upon discharge from the ED. Five choices were offered, as shown in Table 1. In addition, space was pro- vided to record a regimen differing from those provided. Finally, the survey inquired about Prescribing habits with regards to a steroid metered dose inhaler (MDI) at the time of discharge. If answered in the affirmative, respondents were requested to list the brand of steroid MDI and the time the patient was instructed to begin its use.

Statistical analyses were performed using the chi squared

test on the preferred route (ie, IV versus PO) and the preferred outpatient regimen (ie, tapered v nontapered). A P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 208 questionnaires were mailed, with 104 sent to emergency medicine PDs and 104 to private practice EPs. The overall response rate was 74% (153/208). For academic EPs, the response rate was 919c (95/104) and 56% (50/104) for private practice EPs. All but one academic EP was board-certified in Emergency Medicine. Eighty-five percent (81/95) of academic EPs were residency trained in emer-

465

TABLE 1. Steroid Dosing Regimens

|

Day |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|

A

|

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60 mg |

60 mg |

60 mg |

60 mg |

60 mg |

60 mg |

60 mg |

|

B |

60mg |

50mg |

40mg |

30mg |

20mg |

10mg |

|||||||

|

C |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

60mg |

|||||||

|

D |

40mg |

40mg |

30mg |

30mg |

20mg |

20mg |

10 mg |

10 mg |

|||||

|

E |

40mg |

40mg |

40mg |

40mg |

40mg |

40mg |

|||||||

gency medicine, compared with only 43% (25/58) of private practice EPs. Ninety-nine of J43 total respondents (659c) used the IV route initially in the ED, whereas 54 (35%) used the PO route (Table 2). A significantly greater percentage of private practice EPs (45/58 or 789c) used IV rather than oral steroids compared with academic EPs (54/95, 57%, P —

.009). Doses varied, and ranged from 80mg to 250mg for IV methylprednisolone (Solumedrol) and 40mg to l00mg for oral prednisone.

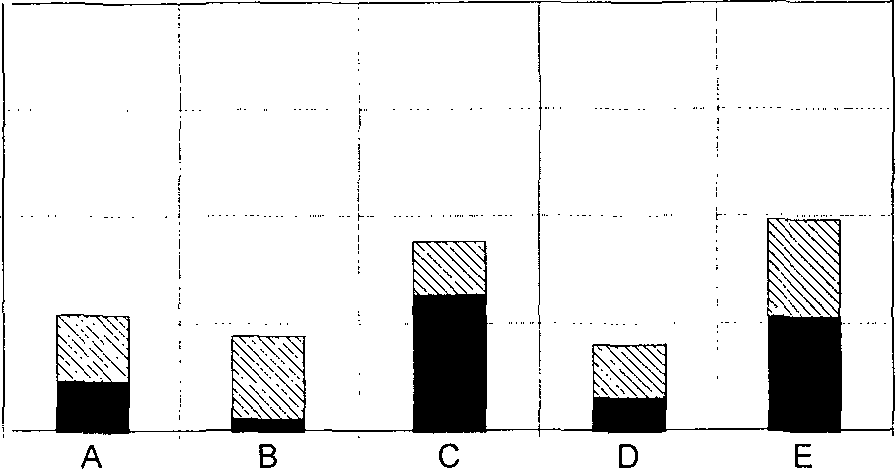

Respondents selected a variety of outpatient steroid reg- imens, as shown in Fig 1. Most participants selected from one of the regimens offered, but 20% (28) chose to write in a unique regimen. The most popular regimens selected were 40 mg of prednisone for 6 days and 60 mg of prednisone for 6 days, both nontapering. Although no particular regimen clearly stands out as the regimen of choice, a significantly greater percentage (P — .0006) of private practice EPs (34/58 or 599c) used a tapering course of steroids compared with academic EPs (29/95 or 31%; see Table 3).

The majority of EPs surveyed did not routinely prescribe steroid MDIs as part of their discharge instructions for the outpatient management of an acute asthma attack. A total of 32% (31) academic and 34% (20) private practice EPs prescribed inhaled steroids. The majority (30/51) of those EPs recommend the patient begin use of the steroid MDI immediately.

DISCUSSION

Although there is universal agreement that steroids are beneficial in the management of acute asthma exacerba- tions, there appears to be little consensus regarding the route and dose for initial ED administration, outpatient regimen, and duration of outpatient steroid therapy. Interestingly, this is essentially the same situation that Collins et al found when he wrote in 1975: “Although synthetic steroids are considered to play an essential part in the treatment of severe asthma unresponsive to bronchodilators, wide vari- ation exists in the dosage of corticosteroids recommended for the treatment of this condition. Neither the best route of administration nor the speed of response to the drug is agreed.””

This study attempted to identify common current prac- tices with regards to steroid use in the management of acute

TABLE 2. IV Versus PO Steroid Administration for Academic and Private EPs

asthma. In addition, we wanted to determine if academic and private practice EPs differ in their management of acute asthma attacks with regards to steroid use.

Steroids are used for their broad action on the inflamma- tory process. Their clinical benefit is exerted based on their ability to suppress cytokines and Inflammatory mediators, thereby diminishing airway hyperresponsiveness. Because this action occurs at a cellular level and involves new transcription, traditional thinking indicates the onset of ste- roid activity requires between 6 and 12 hours, and is un- likely to be observed during the ED stay. Despite this, there is clear evidence that the early use of steroids in the ED for the treatment of acute asthma exaberations results in re- duced admission rates for adults and children.9 ‘? ” ‘? ‘”

The efficacy of oral steroids has compared favorably with IV steroids in numerous studies.3 * In 1988, a JAMA study by Ratto analyzed 77 patients to compare oral versus lV methylprednisolone. Investigators found no difference in the rate of respiratory failure, FEV , days of hospitalization, rate of improvement, or side effects.3 A study of 52 patient in 1986 Lancet by Harrison concluded, “there is no evidence for the continued use of intravenous hydrocortisone in ad- dition to bronchodilator therapy in patients admitted to hospitals with severe asthma.”” More recently, Barnett com- pared 49 patients at a tertiary children’s hospital who re- ceived either 2 mg/kg of IV methylprednisolone or 2 mg/kg of oral prednisone. Four hours after treatment, study groups had similar respiratory rates, oxygen saturations, and FEV . There was no difference in admission rates or relapse.” A recent literature review on corticosteroids in the ED therapy of acute asthma found the oral route provided a similarly beneficial effect on pulmonary function as parenteral ad- ministration.’? A meta-analysis of 6 studies comparing pa- rental versus oral steroids in the treatment of acute asthma revealed no significant difference regarding relapse rate,

100

100

75

Percent

50

25

0

IV PO

|

Academic |

54 (57%) |

41 (43%) |

95 |

||

|

Private |

45 (78%) |

13 (22%) |

58 |

Academic |

Private |

|

Total |

99 (65%) |

54 (35%) |

153 |

||

Total

Dosing Regimen

P .05.

FIGURE 1. Preferred dosing regimen of academic and commu- nity physicians.

TABLE 3. Tapering Versus Nontapering of Outpatient Prednisone

Regimen for Academic and Private Practice EPs

|

Taper |

Nontaper |

Total |

|

|

Academic |

29(31%) |

66 (70%) |

95 |

|

Private |

34(59%) |

24(41%) |

58 |

|

Total |

63(41%) |

90(59%) |

153 |

|

P < .05. |

changes in oxygen tension over treatment period or symp- toms.’^ Despite this evidence, the majority EPs we surveyed preferred the intravenous route. This may be because pa- tients transported via EMS often arrive with IV access already established, or perhaps there is not widespread awareness that oral steroids have been shown to be as effective as IV steroids in the ED setting. Our smdy was not designed to elicit why one route was selected over the another. The most recent NIH guidelines recommend intravenous ste- roids in severe exacerbation and impending respiratory fail- ure.’ In this situation, oral corticosteroids may be difficult or impossible to administer. Similarly, the intravenous route should be used if the patient is complaining of nausea or vomiting. In view of the increased costs, nursing time and potential minor complications of IV therapy, EPs need to be more aware of the efficacy of oral steroids.’^

Steroid tapering has traditionally been taught to avoid relapse, as well as the problem of Adrenal suppression that might follow rapid steroid withdrawal. Evidence is avail- able, however, to indicate that tapering is not necessary.’6 ? O’Driscoll in 1993 studied 35 patients after a 10-day course of prednisone at 40 mg per day.’8 A placebo taper was compared with a 7-day taper decreasing by 5 mg per day. There was no difference in peak expiratory 8ow rates (PEFR), symptom scores, or relapse. Verbeek in 1995, reported that tapering may not be necessary after a short course of prednisone for an acute exacerbation of asthma.'” In 1998, a small study by Cydulka et al compared patients who received an 8-day taper to those who received pred- nisone for 8 days at 40 mg per day. The groups showed no difference in relapse rates, and furthermore, there was no evidence of adrenal suppression in either group.2 From our study, it appears only one-third of academic EPs use a tapering regimen compared with 59% of private practice EPs. Overall 41% of EPs used a tapering regimen. Given the more complex instruction required for tapering, it is likely that compliance suffers and therefore is probably not advis- able in the majority of cases.

Choice of initial ED steroid and dose were variable in our survey. Prednisone seems to be the most popular oral ste- roid, and methylprednisolone seems to be the most common parenteral preparation recommended in the literature for ED management of acute asthma attacks. Our study found the vast majority of EPs use these steroid preparations. Dose comparison studies have shown no benefit for high dose steroids versus moderate to low dose.?’ 2? Current NIH guidelines recommend 120 to 180 mg/day of prednisone in 3 to 4 divided doses for 48 hours, then 60 to 80 mg/day until PEFR reaches 70% of predicted or personal best. Alterna- tively, an outpatient “burst” regimen or 40 to 60 mg per day for 3 to 10 days has been suggested.’

A minority of EPs (33%) prescribe inhaled steroids at dis- charge for outpatient management of acute asthma attacks. Recent studies have explored their use in the ED and for discharge, with encouraging results.2″ 24 2^ A study of Rowe in 1999 evaluated 188 patients in a placebo-controlled, double- blind, randomized clinical trial to determine if inhaled budes- onide for 21 days in addition to oral prednisone for seven days would decrease relapse. Patients in the inhaled corticosteroid group had a 48% relapse reduction, higher quality of life scores, and few J32-agonist activations.26 Such encouraging results would suggest inhaled corticosteroids should be part of our standard discharge regimens.

Our study has several limitations. The method used to collect data for this study was a survey. A common problem with this method is response rate. Although the response rate was excellent for academic EPs, we were able to survey only a small sample of private practice EPs. This difference in response rate may reflect in part, academic EPs greater experience in completing surveys. Common to all surveys, our respondents may not represent a true reflection of non- respondents. In addition, our methodology selected out ACEP members to represent the private practice EPs, and the majority of our respondents were board-certified in emergency medicine. This may not be a Representative sample of physicians practicing emergency medicine.

Asthma management is a dynamic aspect of emergency medicine. Our data may not accurately reflect today’s manage- ment, but should rather be considered a baseline measurement that will undoubtedly change as existing evidence grows.

Based on the results of this study, practice regarding steroid route of administration and dosing regimens is vari- able. It appears the IV route is used frequently in the ED for administration of steroid therapy in the management of acute asthma attacks. This represents an area of potential cost savings, given the numbers of ED visits for asthma attacks annually. Similarly, nearly 40% of EPs use a taper- ing regimen in the outpatient treatment of acute asthma exacerbations. Given the increased complexity of instruc- tions required for tapering, and the apparent efficacy of nontapering regimens, this practice should be reexamined. Further study is recommended to determine if practice is changing to reflect current data.

REFERENCES

- National Institutes of Health National Heart Lung and Blood Institute National Asthma Education and Prevention Program; Au- thor, Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma: Expert panel report 2. Bethesda, MD, 1997, p 146

- Dunlap NE, Fulmer JD: Corticosteroid therapy in asthma. Clin Chest Med 1984;5:669-683

- Becker JM, Arora A, Scarfone RJ, et al: Oral versus intrave-

nous corticosteroids in children hospitalized with asthma. J Allergy Clin lmmunol 1999;103:586-590

- Jonsson S, Kjartansson G, Gislason D, et al: Comparison of

the oral and intravenous routes for treating asthma with methylpred- nisolone and theophylline. Chest 1998;94:723-726

- Ratto D, Alfaro C, Sipsey J, et al: Are intravenous corticoste- roids required in Status asthmaticus? JAMA 1988;260:527-529

- Harrison BD, Stokes TC, Hart GJ, et al: Need for intravenous hydrocortisone in addition to oral prednisolone in patients admitted to hospital with severe asthma without Ventilatory failure. Lancet 1986;1:181-184

- Barnett PL, Caputo GL, Baskin M, et al: Intravenous versus

oral corticosteroids in the mangement of acute asthma in children. Ann Emerg Med 1997;29:212-217

- Collins JV, Clark TJH, Brown D, et al: The use of corticoste-

roids in the treatment of acute asthma. QJ Med 1975;174:259-273

- Littenberg B, Gluck EH: A controlled trial of methylpred- nisolone in the emergency treatment of acute asthma. N Engl J Med 1986;314:150-152

- Schneider SM, Pipher A, Britton HL, et al: High dose meth- ylprednisolone as initial therapy in patients with acute broncho- spasm. J Asthma 1988;25:189-193

- Tal A, Levy N, Bearman JE: MethylPrednisolone therapy for acute asthma in infants and toddlers: A controlled clinical trial. Pediatrics 1990;86:350-356

- Storr J, Barry W, Barrell E, et al: Effect of a single oral dose of prednisolone in acute childhood asthma. Lancet 1987;1:879-882

- Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme FM, et al: Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticoste- roids (Cochrane review), in The Cochrane Library, issue 4. Oxford, Update Software, 2000

- Rodrigo G, Rodrigo C: Corticosteroids in the emergency de- partment therapy of acute asthma. Chest 1999;116:285-295

- Rowe BH, Keller JL, Oxman AD: Effectiveness of steroid therapy in acute exacerbations of asthma: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med 1992;10:301-310.

- Lederle FA, Pluhar RE, Joseph AM, et al: Tapering of corti- costeroid therapy following exacerbation of asthma. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 1987;147: 2201-2203

- Hatton MQF, Vathenen AS, Allen MJ, et al: A comparison of ‘abruptly stopping’ with ‘tailing off’ oral corticosteroids in acute asthma. Resp Med 1995;89:101-104

- O’Driscoll BR, Kalra S, Wilson M, et al: double-blind trial of steroid tapering in acute asthma. Lancet 1993;341:324-327

- Verbeek PR, Geerts WH: Nontapering versus tapering pred- nisone in acute exacerbations of asthma: A pilot trial. J Emerg Med 1995;13:715-719

- Cydulka RK, Emerman CL: A pilot study of steroid therapy after emergency department treatment of acute asthma: Is a taper needed? J Emerg Med 1998;16:15-19

- Marquette CH, Stach B, Cardot E, et al: High-dose and low-dose Systemic corticosteroids are equally efficient in acute severe asthma. Eur Respir J 1995;8:22-27

- Emerman CL, Cydulka RK: A randomized comparison of 100-mg vs 500-mg dose of methylprednisolone in the treatment of acute asthma. Chest 1995;107:1559-1563

- Afilalo M, Guttman A, Colacone A, et al: Efficacy of inhaled steroids (beclomethasone dipropionate) for treatment of mild to moderately severe asthma in the emergency department: A ran- domized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med 1999;33:304-309

- Rodrigo G, Rodrigo C: Inhaled flunisolide of acute severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;157:698-703

- Sung L, Osmond MH, Klassen TP: Randomized, controlled trial of inhaled budesonide as an adjunct to oral prednisone in acute asthma. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:209-213

- Rowe BH, Bota GW, Fabris L, et al: Inhaled budesonide in addition to oral corticosteroids to prevent asthma relapse following discharge from the emergency department: A randomized con- trolled trial. JAMA 1999;281:2119-2126