A systematic review of foam dressings for partial thickness burns

a b s t r a c t

Background: partial thickness burns are the most common form of thermal burns. Traditionally, dressing for these burns is simple gauze with silver sulfadiazine (SSD) changed on a daily basis. Foam dressings have been proposed to offer the advantage of requiring less frequent dressing change and better absorption of exudates.

Objective: To compare the impact of silver-containing foam dressing to traditional SSD with gauze dressing on wound healing of partial thickness burns.

Methods: We performed a systematic literature search using PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library database and Google Scholar for trials comparing traditional SSD dressings to that of silver- containing foam dressing on wound healing in partial thickness burns b25% of the body surface area. We ex- cluded studies that enrolled burns involving head, face, and genitals; burns older than or equal to 36 h, non- thermal burns, and Immunocompromised patients. Quality of trials was assessed using the GRADE criteria. The main outcome, complete wound healing, is reported as percentages of wound with complete epithelialization after the follow up period. Relative risks of complete healing are also reported with respective 95% CI. Time to healing and pain score before, during, and after dressing change at each follow up visit are compared between the groups (means with standard deviation or medians with quartiles).

Results: We identified a total of 877 references, of which three randomized controlled trials (2 combined pediatric and adult trials and 1 adult trial) with a total of 346 patients met our inclusion criteria. All three trials compared silver-containing foam dressing to SSD and gauze on partial thickness burns. Moderate quality evidence indicated no significant difference in wound re-epithelialization between the groups across all three trials as confidence in- tervals for the relative risks all crossed 1. Although pain scores favored foam dressing at the first dressing change (7 days), there was no significant difference between the groups at the end of the treatment period at 28 days. Time to wound healing was also similar across the three trials with no statistical difference. infection rates fa- vored the foam-dressing group, but data were inconsistent.

Conclusion: Moderate quality evidence indicates that there is no significant difference in wound healing between silver-containing foam dressing and SSD dressing. However, foam has the added benefit of reduced pain during the early treatment phase and potentially decreased Infection rates.

(C) 2019

Background

There are nearly 486,000 burn injuries annually requiring medical treatment in the United States, with the majority (77%) being thermal injuries [1]. A thermal burn is defined as traumatic injury to the skin, or other tissues that is caused by contact with an external heat source. The most common injury is a partial-thickness burn, which destroys structures under the epidermis and can result in scarring and infection [2]. These injuries can be painful and disfiguring. Techniques that opti- mize wound healing may decrease burn sequela. The ideal dressing is one that promotes wound healing at a rapid pace, minimizes pain

* Corresponding author at: Department of Emergency Medicine, State University of New York, Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (P. Chaganti), [email protected] (S. Zehtabchi).

during dressing change, absorbs excessive exudate, controls bacterial burden, and prevents any local or systemic adverse reactions [2].

Dressings allow for a protective barrier until tissue integrity is re- stored, or until Skin grafting can take place (if necessary). Problems such as Wound infection, poor patient compliance, wound desiccation, and inappropriate wound care can impact function (particularly in burns involving extremities) and cause serious scars, deformities, or prolonged healing [3]. Therefore, it is essential for the clinician to care- fully consider the optimal dressing.

There are numerous types of dressings for partial thickness burns. Silver sulfadiazine (SSD) cream has been widely used since the 1960s to prevent wound infection [4]. However, recent studies have shown that SSD has a damaging effect on regenerating keratinocytes and delays wound healing [5]. In addition, traditional dressings with SSD require daily dressing changes that adhere to the wound causing a disruption in the granulation process [4]. There is limited evidence to support the

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.04.014 0735-6757/(C) 2019

superiority of SSD compared to placebo or non-antibiotic controls (such as wet gauze) in improving wound healing or re-epithelialization rates [6].

Foam dressings have the ability to absorb exudate, which allows for less frequent dressing changes [7]. The non-adhesive nature of foam po- tentially causes less wound and surrounding skin damage during dress- ing changes [7]. This could potentially prevent additional tissue damage during dressing change and allow the tissue to heal without disturbance [8]. This in turn may reduce pain and discomfort. It has also been sug- gested that the moist environment created by the foam dressing is con- ducive to wound healing. A further potential benefit is that foam provides a flexible barrier that protects the wound from contamination while accommodating movement [7].

Most foam dressings are made of highly absorbent polyurethane. Other types of foams include: hydrofiber which transforms into gel upon contact with a moist wound, dressings with layers of polyurethane and hydrofiber, and hydrocellular which contains layers of polyure- thane foam and polyurethane film. Generally, foam dressings are cov- ered with gauze and tape to secure it in place. Some are waterproof with an adhesive border and do not require a cover dressing. Some products contain antibacterial agents such as silver while others are antibacterial-free (Appendix 1) [4].

The disadvantages of foam include: drying out the wound if no or minimal exudate is present, and maceration of the surrounding skin if the dressing becomes saturated with exudate [4].

Most foam dressings are impregnated with silver (Ag) as this ele- ment has been shown to decrease the tissue bacterial bioburden and po- tentially accelerate wound healing [9]. Despite the growing number of silver-containing dressings for variety of wounds such as burns, chronic ulcers, etc., the evidence supporting their clinical use in burn patients is not based on solid evidence [10,11].

The primary objective of this systematic review is to compare the rate of re-epithelialization (complete healing) and time to wound healing of two treatment options, foam dressings versus silver sulfadia- zine with gauze, in patients of all ages who have sustained second- degree thermal burns. The secondary objectives are to compare the level of pain the patient experiences during the dressing change and in- fection rate between the two groups.

Methods

We developed a systematic review protocol following the recom- mendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We also registered our sys- tematic review at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID: CRD42018098609) before the start of the pro- ject [12].

Inclusion & exclusion criteria

The research question posed by this review is the following: In pa- tients with partial thickness burns (Population), does application of foam dressing (Intervention) in comparison to traditional silver- sulfadiazine and non-foam dressing (Comparison) improve wound healing (Outcome)?

For patient population, we selected trials that enrolled patients of any age with partial thickness thermal burns covering b25% of the body surface area. We excluded studies that enrolled patients with burns to the head, face, and Genital area; burns equal to or older than 36 h, chemical or electrical burns, and patients with an immunocompro- mised state (immunodeficiency, diabetes, HIV, chronic glucocorticoid use, on immunosuppressive agents). For intervention, we considered foam dressings of any brand name applied at any frequency. We did not specifically include antibiotic-containing foam dressings but planned to perform a subgroup analysis to assess the impact of foam dressings with and without antibiotics on wound healing separately.

For comparison, we considered any type of traditional dressing (not containing foam) with silver-sulfadiazine, as this is the most common type of dressing used worldwide. We only included trials that enrolled subjects randomized to foam dressing or silver sulfadiazine plus dress- ing and assessed the outcome of complete wound healing (percentage of patients with complete wound epithelialization) at the end of the fol- low up period or reported the time to complete healing. We were also interested in the level of pain before, during, and after dressing change, and infection rate (secondary outcomes).

Literature search

A complete and systematic literature search of articles was con- ducted without any limit on year of publication or publication language. Search strategies were developed for each database with the help of an expert librarian. The following databases were used to perform the liter- ature search: PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Web Of Science, Cochrane Li- brary database, and Google Scholar. We selected medical subject heading (MeSH) terms to include the concepts of foam, dressings, and burns. The PubMed search strategy is provided in Appendix 2.

Grey literature search involved screening the proceedings of scien- tific conferences of the relevant disciplines (emergency medicine, burn, surgery, plastic surgery, and dermatology) within the last 5 years to identify unpublished trials. We also screened the references of the relevant articles and contacted experts in the field inquiring about ongoing or unpublished trials. We also searched clinicaltrials. gov for ongoing registered trials.

All the citations were transferred to a citation manager (EndNote) and the duplicates were removed. Two reviewers (PC and IG) indepen- dently screened the citations based on their titles and abstracts. A third reviewer SZ resolved disagreements. We reviewed relevant articles or those with questionable relevancy in their entirety to select those meet- ing criteria for the systematic review.

Using the flow diagram proposed by PRISMA, the total number of ci- tations including those from the grey literature, as well as the number of citations excluded based on review of their titles, abstracts, and full ar- ticles was documented.

When the methodology or the reported data were not clear, we attempted to contact the authors to clarify or to obtain the missing information.

Quality assessment

We used Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria to assess the quality of the included tri- als [13]. Two authors (PC & SZ) separately assessed the quality of the in- cluded trials and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data abstraction

Two reviewers (PC and SZ) abstracted data from qualifying trials that met inclusion criteria. Each reviewer crosschecked the data to look for discrepancies. A summary of the characteristics of the qualify- ing studies can be seen in Table 1. Retrieved data included percentage of patients with complete wound healing; time to wound healing, pain scores during each week of the trial, and infection rates.

Data analysis

The data are reported as relative risks with their respective 95% con- fidence intervals for percentage of patients with complete healing at the end of the follow up period. We report time to healing and pain with means or medians and mean differences with 95% confidence interval if data were reported by the original trials. We planned to pool the data if clinical heterogeneity was deemed to be low among the trials.

Characteristics of the included trials.

|

Trial |

Patients |

Baseline Wound management |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Outcome |

Follow up |

|

Silverstein |

Multicenter (10 centers) in USA. |

MAg group: cleansed the wound |

Dressing with |

Dressing |

Time to wound healing (mean), |

21 days post burn |

et al. [14]

Tang et al. [2]

Yang et al. [15]

Inclusion: patients older than 5 years old with Burn injury (thermal origin) within 36 h of enrollment, and a second-degree burn area of 2.5 to 20% of TBSA or Patients with burns covering between 3 and 25% of TBSA, allowing for up to 10% of TBSA to be third-degree burn.

Exclusions: chemical or electrical burn; clinically infected burn; treatment of the burn with an active agent before study entry (i.e., SSD within 24 h of randomi- zation); and pregnancy

Multicenter (11 centers) in China. Inclusion: patients 5-65 yo with burn injury (thermal origin) within 36 h of enrollment, and a second-degree burn with 2.5 to 25% of TBSA, allowing for up to 10% of TBSA to be third-degree burn.

Exclusions: chemical or electrical burn; clinically infected burn; treatment of the burn with an active agent before study entry (i.e., SSD within 24 h of randomi- zation); pregnancy and immuno- compromised state

Patients treated at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, China from June 2010 to Sept 2014.

Inclusion: patients aged 18-60 yo with second degree burns on

non-joint regions; total burn b25% TBSA, wound infections or ulcers. Exclusions: chemical, electric, or radiation burns; chronic medical conditions or immunodeficiency, burns on face/head/perineum/joints, pregnant women and mentally unstable

according to standard practice and skin dried thoroughly. The adherent side of the dressing was applied to the wound, without tension and with an overlap of at least 2 cm onto intact skin.

Dressing changes of MAg every 7 days

SSD group: the burn area cleansed and covered with SSD cream once to twice daily to a thickness of approximately 2 mm; covered with a gauze pad and gauze wrap. At dressing change, previously applied SSD was removed before reapplication. Dressing change daily after discharge.

MAg group: debrided and cleansed according to standard practice and skin dried thoroughly. Dressing applied in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Dressing cut to enable conformity to body contours. Gauze used as secondary dressing for fixation. Dressing changes of MAg every 7 days

SSD group: the burn area debrided and cleansed according to standard practice and skin dried thoroughly and covered with 1% SSD cream once daily; covered with a gauze pad and gauze wrap.

Wounds sterilized, debrided, cleansed.

Foam group: Dressing tailored to extend beyond 2-5 cm larger than wound, covered, fixed, protected by secondary dressing. Dressing changed once per day to once per week.

SSD group: wounds wiped with 1% silver sulfadiazine cream, bandaged with gauze. Changed at least once per day.

Mepilex-Ag

Dressing with Mepilex-Ag

Silver-containing soft silicone dressing

with SSD

Dressing with SSD

Dressing with SSD

percentage of healed burns (median), pain (mean), comfort, ease of product use, infection rate, dressing adherence, flexibility and conformability of dressing, cost, and adverse event

Time to wound healing (median), percentage of healed burns (median), pain (mean), number of dressing changes, tolerability and performance of dressings, and periwound status

Time to wound healing (mean), percentage of healed burns (median), pain (mean), wound healing by area, infection rate, periwound status, comfort

or until full reepithelialization occurred

28 days post burn or until full reepithelialization occurred

28 days post-burn

Abbreviations: TBSA: total body surface area, SSD: Silver sulfadiazine.

Results

The literature search identified 877 articles. We excluded 146 dupli- cate articles and removed another 718 articles based after reviewing their titles and/or abstracts. We reviewed 13 full-length articles in their entirety and found three trials that met the Inclusion/exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Two trials published in Spanish and Russian were trans- lated by native speakers but did not meet the inclusion criteria.

The three trials included in our systematic review enrolled 346 patients in aggregate [2,14,15]. All three studies were controlled tri- als, which all enrolled adult patients [2,14,15] with two trials enroll- ing children as well [2,14]. Only two of the trials explicitly described the method of randomization [2,14]. Two trials were conducted in China [2,15] and the third was conducted in a Burn center in the United States [14]. All three trials compared silver-containing foam dressing to silver sulfadiazine and gauze on second-degree burn pa- tients. We did not identify any trial that compared simple foam

dressing (not containing antibiotics) to silver sulfadiazine dressing or simple wet gauze.

The patients enrolled in the included trials were evaluated on weekly follow-up visits for a total of 28 days in two studies [2,15], and 21 days in the study by Silverstein et al. [14] Each visit documented de- gree of wound healing, pain scores, and infection rate [2,14,15]. The re- sults of the quality assessment of the included trials using GRADE criteria are listed in Table 2.

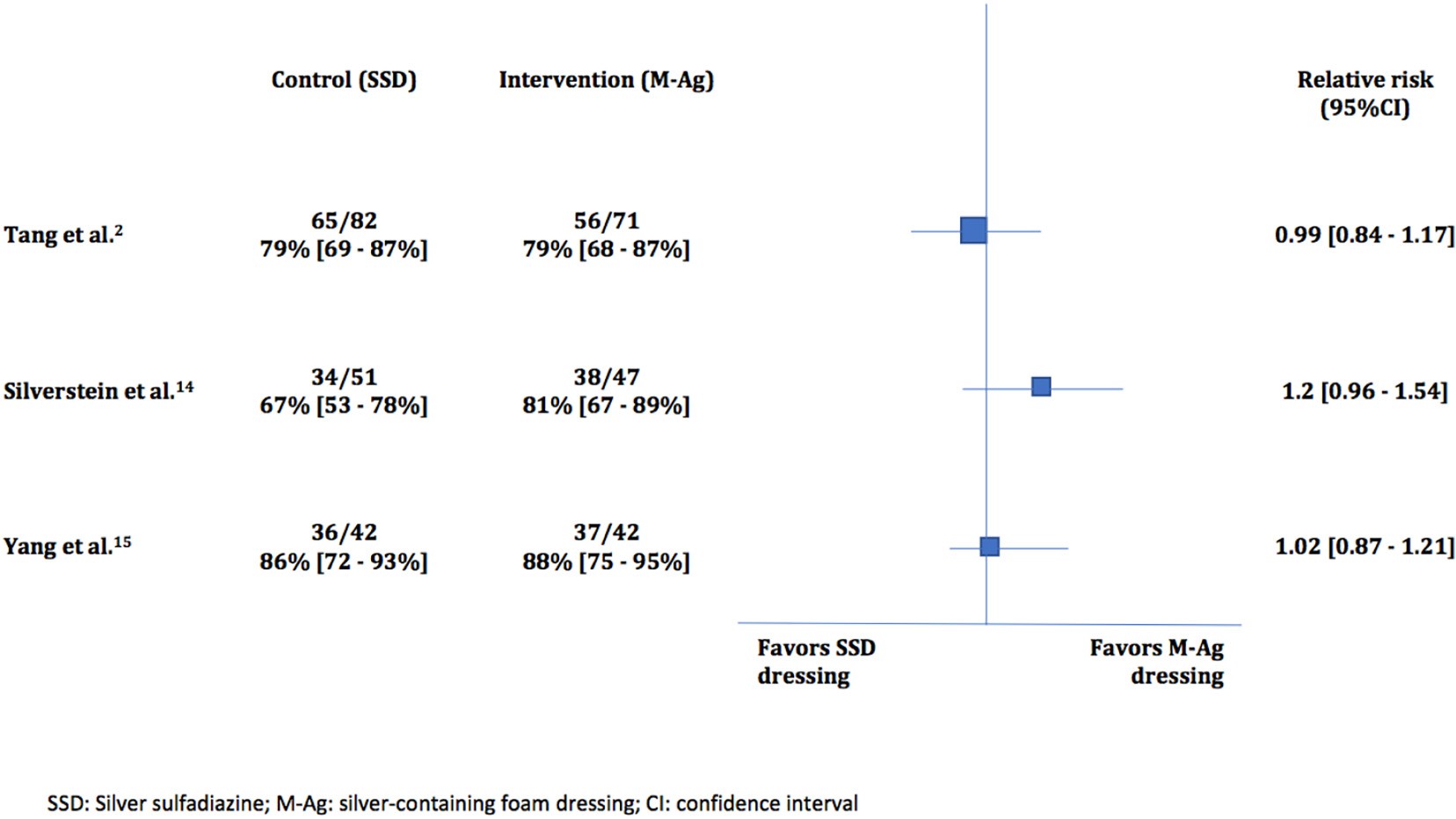

The percentage of patients with complete healing at the end of the follow up period was not significantly different between the groups in all three trials as confidence intervals for the relative risks all crossed 1 (1.0 [95%CI, 0.85-1.17] [2], 1.2 [95%CI, 0.95-1.53] [14], and 1.0 [95%

The method of reporting the outcome of time to healing differed be- tween the trials. One trial reported mean days to complete healing with- out standard deviation or mean difference [14]. Another trial only reported median days to complete healing without reporting quartiles

Fig. 1. Flow diagram representing the process of selecting the trials.

or interquartile ranges [2]. Only one trial reported means and standard deviations for days to complete healing [15]. All 3 trials reported p values after comparing the time to healing between the groups [2,14,15]. Yang et al. reported a statistically significant difference be- tween the group for this outcome (Table 3) and the difference between the groups for time to complete healing were not statistically significant in the other two trials [2,14,15]. Unfortunately, we were not able to ob- tain the missing information from the authors despite repeated at- tempts to contact them.

Table 2 Quality assessment of the selected studies of foam versus gauze dressings using the Grad- ing of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria.

The method of reporting pain before, during, and after dressing change significantly varied between the trials (Table 4). However, all three trials used visual analog scales for adult patients. Silverstein et al. and Tang et al. used the Wong Baker faces scale for pediatric pa- tients. Two trials reported mean difference of pain scores with corre- sponding 95% confidence intervals at different follow up points [2,15]. In addition, one of these trials reported before, during, and after dressing change pain scores [2]. Reviewing the data reported by Tang et al. re- veals that patients in the foam dressing group experienced significantly less pain particularly during and after the dressing change [2]. In the trial by Silverstein et al., lower pain scores during and after the dressing change were statistically significant 7 days after the burn injury (Table 4) [14]. Lastly, Yang et al. measured the pain scores on days 0, 7, 14, 21 and 28 and reported that the patients in the foam dressing group experienced significantly less pain during follow up visits on days 7, 14, and 21 before and during dressing change (no significant dif- ference between the groups at day 0 and day 28) [15]. Administration of pain medication during dressing change was not reported in any of the three trials.

Data pertaining to infection rates of the wound were limited. Two of the trials reported rate of bacterial growth in foam and silver sulfadia- zine groups [2,15]. Yang et al. reported that, while initial bacterial growth from cultured wound secretions was equal in both groups, the foam group had a significantly lower rate of bacterial growth at 28 days (5.9% vs 11.6%) [15]. Tang et al. report that 8 patients (11%) from the foam dressing group experienced a new symptom of wound inflammation (erythema, edema, warmth, foul odor) compared with 14 patients (17%) in the SSD group [2].

Discussion

We found three studies that met our inclusion criteria for this sys- tematic review [2,14,15]. According to our assessment, the methodolog- ical quality of these studies were moderate. These trials showed that wound healing was similar between foam dressing and silver- sulfadiazine and gauze in patients with partial thickness burns. All trials demonstrated similar degrees of re-epithelialization at the end of the study periods.

However, other trials demonstrate silicone foam dressings to have efficient rates of wound healing. For example, in a randomized trial comparing dressings with non silicone vs silicone interface for pediatric burns, authors reported slower re-epithelialization rates and bleeding from the wound bed duRing removal of non silicone dressings [16].,In a different prospective noncomparative study, silver-based foam dress- ing was found to have a rapid Healing time of 7 days in 50% of patients [17]. Although these trials demonstrate favorable outcomes for silicone-based foam dressings, their comparative control treatment did not meet inclusion criteria for our systematic review.

All three studies in our analysis reported foam dressing to be less painful and more comfortable for patients, particularly in the earlier stages of healing. While the unique qualities of the foam dressing sup-

Randomized

controlled trials

Possible limitations

Possible limitations of randomized trials

Lack of allocation concealment

port this finding theoretically, because of the limitations in reporting the cessation of pain by the included trials, drawing a definitive conclu- sion on this outcome is not possible. Gee Kee et al. offers insight behind the reasoning of this pain-free dressing, “Silicone adheres to normal in- tact skin and remain in situ on the surface of a wound but do not adhere to it, maintaining a moist wound environment while providing a less traumatic removal and subsequently less epidermal damage” [16].

Trials Existing limitations

Outcomes reported Quality of

evidence

Reason for downgrade

Other studies have also reported less pain associated with foam dressings. A multicenter observational trial by Morris et al. found that

Silverstein et al. [14]

Tang et al. [2]

Yang et al. [15]

2, 3,5 Complete healing, time to healing, pain

2, 5 Complete healing, time to healing, pain

1, 2,5 Complete healing, time to healing, pain

Moderate Imprecision and

other limitations Moderate Imprecision and

other limitations Moderate Imprecision and

other limitations

foam dressings can minimize trauma and pain during dressing change

in pediatric patients with wounds and skin injuries including burns [18]. In this study, the mean Pain severity scores were significantly lower at the first dressing change than at baseline. This study reported that over 99% of the foam dressing changes were deemed to be “atraumatic”. Comfort, ease of use, ease of removal, patient comfort,

Fig. 2. Percentage of patients with complete healing among the included trials.

and overall experience with the dressing were rated as “good” to ‘very good’ at the vast majority of final evaluations [18]. Glat et al. reported minimal pain and minimal medication use associated with foam dress- ing use in pediatric patients with partial thickness burns [17]. It is im- portant to keep in mind that reduced pain during the dressing change might translate into a reduction pain medication use [2,14,15].

Due to the incomplete reporting of bacterial growth rate among the three included trials, we cannot make conclusive statements in regards to the effect of foam dressings on bacterial growth. However, a 2017 lit- erature review of silver-containing foam dressings examined 9 studies that reported in vitro test results, all of which demonstrate that silver- containing foam dressings have both rapid and sustained activity against a range of wound pathogens. They can also successfully prevent biofilm formation [7]. A prospective observational study by Meuleneire et al. showed that the use of silver foam dressings on infected wounds, (deemed to only require local antibiotics), resulted in resolution of in- fection in nearly 90% of the wounds [19].

Additionally, foam dressings can be left in place for up to seven days [20]. Therefore, the number of dressing changes is significantly less compared to traditional dressings, which require daily dressing changes. The longer wear time and flexibility of foam dressings allows patients to return to normal activity sooner [4]. This may be especially important to active individuals and pediatric patients. Tang et al. found that foam with silver was rated higher than silver sulfadiazine and gauze by clinicians in terms of ease of application, lack of dressing adherence, ease of removal and overall experience. It was also rated fa- vorably by patients in terms of anxiety during dressing change, ease of movement while wearing it, the dressing remaining in place, and lack of stinging or burning while wearing it [2].

Foam appears to have few disadvantages. It is important for foam dressings to be kept dry, and therefore, may not be advisable for pa- tients who are not compliant.

Time to healing (days) among the included trials

Cost is an important factor when choosing a treatment strategy. Silverstein et al. performed a cost effectiveness analysis and reported significant reduction in cost (including dressing supplies and labor) for patients assigned to the foam group [14]. This analysis was per- formed only on a fraction of the enrolled patients (n = 40/101) but re- vealed an average savings of $240 per patient. Although this does not sound like much, since foam also improved the rate of complete healing

Table 4

Summary of self-reported pain during varioUS time points in each study comparing foam dressing to traditional silver sulfadiazine dressing.

Study Pain difference (mean with CI)

Tang et al. [2] Day 0

Before assessment 7.6 [-0.3-15.5]

Day 7

- Before removal 12.2 [5.9-18.4]

- During removal 20.7 [13.4-28.0]

- After removal 17 [9.5-24.5]

Day 14

- Before removal 7.9 [2.9-12.9]

- During removal 13.9 [7.3-20.5]

- After removal 11.9 [5.7-17.9]

Day 21

- Before removal 3.8 [-1.7-9.2]

- During removal 9.4 [2.7-16.2]

- After removal 6.2 [0.2-12.2]

Day 28

- Before removal 4.2 [-0.9-9.4]

- During removal 9.9 [3.2-16.6]

- After removal 6.4 [0.1-12.7]

Silverstein et al. [14] Day 7

- During removal 20.9 (p = 0.018)

- During wear 13.5 (p = 0.048)

Yang et al. [15]

|

Study |

Control (SSD) |

Intervention (Mag) |

p value |

Day 0 Day 7 |

2.2 [-6.2-10.6] 15.6 [10.4-20.9] |

|

Tang et al. [2] |

15 (median) |

16 (median) |

0.74 |

Day 14 |

13.9 [11.3-16.5] |

|

Silverstein et al. [14] |

17 (mean) |

13 (mean) |

N0.05 |

Day 21 |

7.5 [5.7-9.3] |

|

Yang et al. [15] |

25 +- 4 (mean +- SD) |

22 +- 3 |

b0.05 |

Day 28 |

0.7 [-0.09-1.5] |

in this trial, the overall incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was in favor of foam dressing protocol by a wide margin. Sheckter et al. conducted a Decision analysis with an incremental cost-utility ratio comparing silver foam dressings with silver sulfadiazine in partial-thickness burn pa- tients with total body surface area of burn b20% that also favors the use of foam dressings [21]. In this analysis, the Health benefits included successful healing, infection, and non-infected delayed healing requir- ing either surgery or conservative management. The probabilities of these outcomes were matched with Medicare Current Procedural Ter- minology (CPT) reimbursement codes (cost) and patient-derived utili- ties (defined as an assigned value between 0 [death] and 1 [perfect health] based on the state of health) to fit into the decision model. Util- ities were obtained using a visual analog scale during patient interviews. The investigators calculated the expected cost and Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), a roll-back method. This study concluded that foam sil- ver dressings (e.g. Mepilex) offer a cost-effective means of treating partial-thickness burns. These dressings offered a higher utility than silver-sulfadiazine and gauze, as well as a better quality of life in burn treatment [21].

Limitations

Burn depth is an important factor that must be taken into account when assessing a burn injury. The burn depth may change after the ini- tial injury. None of the three included trials attempted to blind the out- come assessors, nor did they attempt to minimize assessor bias. Therefore, their findings were subject to bias. The method of reporting the data by the included trials was vastly different and somewhat in- complete, especially in regards to the outcomes of time-to-healing, pain, and infection rates. Because of the obvious clinical heterogeneity between the trials, poor data reporting, and small aggregate sample size, pooling of the data was not possible.

Further clinical trials are warranted to help validate the clinical evi- dence with larger sample sizes and more robust methodologies. It is also necessary to compare the effectiveness of foam dressings to that of wet gauze without any antibiotics or neutral non-adhesive petroleum-based dressings.

Conclusion

The existing evidence demonstrate that there is no significant differ- ence in the primary outcome of overall wound healing between silver containing-foam dressing and silver sulfadiazine dressing. Additionally, foam appears to have the added benefit of reduced pain associated with dressing change and potentially decreased infection rates (secondary outcomes).

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ajem.2019.04.014.

This manuscript was not presented elsewhere.

The research was not supported by outside funding or grants. PC re- ports no conflict of interest.

PC, JC, and SZ conceived the study and designed the trial. SZ drafted the MeSH terms and PC and IG performed the literature search. PC and SZ managed the data, analyzed the data, and per- formed statistical calculations. PC drafted the manuscript, and JC and SZ contributed substantially to its revision. PC takes responsibil- ity for the paper as a whole.

Appendix 1. Foam dressing products

Antibiotics Without antibiotics

Hydrofera BLUE foam (polyurethane Mepilex (without Ag) foam, methylene blud, gentian violet) Aquacel (without Ag) IodoFoam (iodine) Allevyn non-adhesive

Acticoat (Ag) Biatin non-adhesive Algidex (Ag, alginate, maltodextrin) Tielle non-adhesive Allevyn (Ag) Lyofoam max

Aquacel (ionic Ag) Spyrosorb foam

Biatin +/- silicone (Ag) ComfortFoam border

Bordered foam (Ag) TRIACT foam with silicone border

Cutimed siltec sorbact 3M Tegaderm high performance silicone/foam non-adhesive dressing

HydraFoam (Ag) Advazorb border hydrophilic foam dressing

Kendall AMD antimicrobial foam (PHMB) AMERX foam dressings MediPlus super foam Ag+ Bordered foam

Mepilex foam (Ag) Cardinal health silicone bordered foams

PolyMem silver (Ag) CoFlex AFD

Optifoam (Ag) CovaWound foam Restore non-adhesive foam with silver Cutimed cavity/siltec RTD wound dressing (Methylene blue, DermaFoam

gentian violet, silver)

Shapes by PolyMem oval silver (Ag) DermaLevin ULTRA silver DevraSorb

Gentell Lo profile/silicone foam HydraFoam

HydroCell foam HydroTac

Kendall border foam KerraFoam

McKesson hydrocellular foam Mediplus comfort border MPM non/bordered foam NoTraum silicone

Optifoam OXYGENESYS

PermaFoam Polyderm Polymem Restore foam

Shapes by polymem Silon dual-dress 50 Simpurity foam ULTRA

XTRASORB super absorbent - foam (non/adhesive)

XuSorb foam

References

- American Burn Association. Burn incidence and treatment in the United States: 2016 fact sheet. Available at: https://ameriburn.org/who-we-are/media/burn-incidence- fact-sheet/, Accessed date: 6 February 2017.

- Tang H, Lv G, Fu J, Niu X, Li Y, Zhang M, et al. An open, parallel, randomized, compar- ative, multicenter investigation evaluating the efficacy and tolerability of Mepilex Ag versus silver sulfadiazine in the treatment of deep partial-thickness burn injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;78:1000-7.

- Hermans MH. Treatment of burns with occlusive dressings: some pathophysiologi- cal and quality of life aspects. Burns 1992;18:S15-8.

- Wasiak J, Cleland H, Campbell F, Spinks A. Dressings for superficial and partial thick- ness burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:CD002106.

- Wasiak J, Cleland H. Minor thermal burns. Clinical evidence. BMJ Publishing Group; 2005.

- Miller AC, Rashid RM, Falzon L, Elamin EM, Zehtabchi S. Silver sulfadiazine for the treatment of partial-thickness burns and venous stasis ulcers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;66:e159-65.

- Davies P, McCarty S, Hamberg K. Silver-containing foam dressings with Safetac: a re- view of the scientific and clinical data. J Wound Care 2017;26:S1-S32.

- Rippon M, Davies P, White R. Taking the trauma out of wound care: the importance

of undisturbed healing. J Wound Care 2012;21:359-60.

Castellano JJ, Shafii SM, Ko F, Donate G, Wright TE, Mannari RJ, et al. Comparative evaluation of silvercontaining antimicrobial dressings and drugs. Int Wound J 2007;4:114-22.

- Leaper DJ. Silver dressings: their role in wound management. Int Wound J 2006;3: 282-94.

- Norman G, Christie J, Liu Z, Westby MJ, Jefferies JM, Hudson T, et al. Antiseptics for burns. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;7:CD01182.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta- analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4(1).

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE guide- lines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence-study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:407-15.

- Silverstein P, Heimbach D, Meites H, Latenser B, Mozingo D, Mullins F, et al. An open, parallel, randomized, comparative multicenter study to evaluate the cost- effectiveness, performance, tolerance, and safety of a silver-containing soft silicone foam dressing (intervention) vs silver sulfadiazine cream. J Burn Care Res 2011; 32:617-26.

- Yang B, Wang X, Li Z, Qu Q, Qiu Y, et al. Beneficial effects of silver foam dressing on healing of wounds with ulcers and Infection control of burn patients. Pak J Med Sci 2015;31:1334-9.

- Gee Kee EL, Kimble RM, Cuttle L, Khan A, Stockton KA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of three burns dressings for partial thickness burns in children. Burns 2015;41: 946-55.

- Glat PM, Zhang SH, Burkey BA, Davis WJ. Clinical evaluation of a silver- impregnated foam dressing in paediatric partial-thickness burns. J Wound Care 2015;24:S4-S10.

- Morris C, Emsley P, Marland E, Meuleneire F, White R. Use of wound dressings with soft silicone adhesive technology. Paediatr Nurs 2009;21:38-43.

- Meuleneire F. An observational study of the use of a soft silicone silver dressing on a variety of wound types. J Wound Care 2008;17:535-9.

- Molnlycke Mepilex Ag product data sheet report PD-358735-10. Available at https:// www.molnlycke.us/products-solutions/mepilex-transfer-ag/, Accessed date: 30 No- vember 2018.

- Sheckter CC, Van Vliet MM, Krishnan NM, Garner WL. Cost-effectiveness comparison between topical silver sulfadiazine and enclosed silver dressing for partial-thickness burn treatment. J Burn Care Res 2014;35:284-90.